Hydrodynamic lubrication

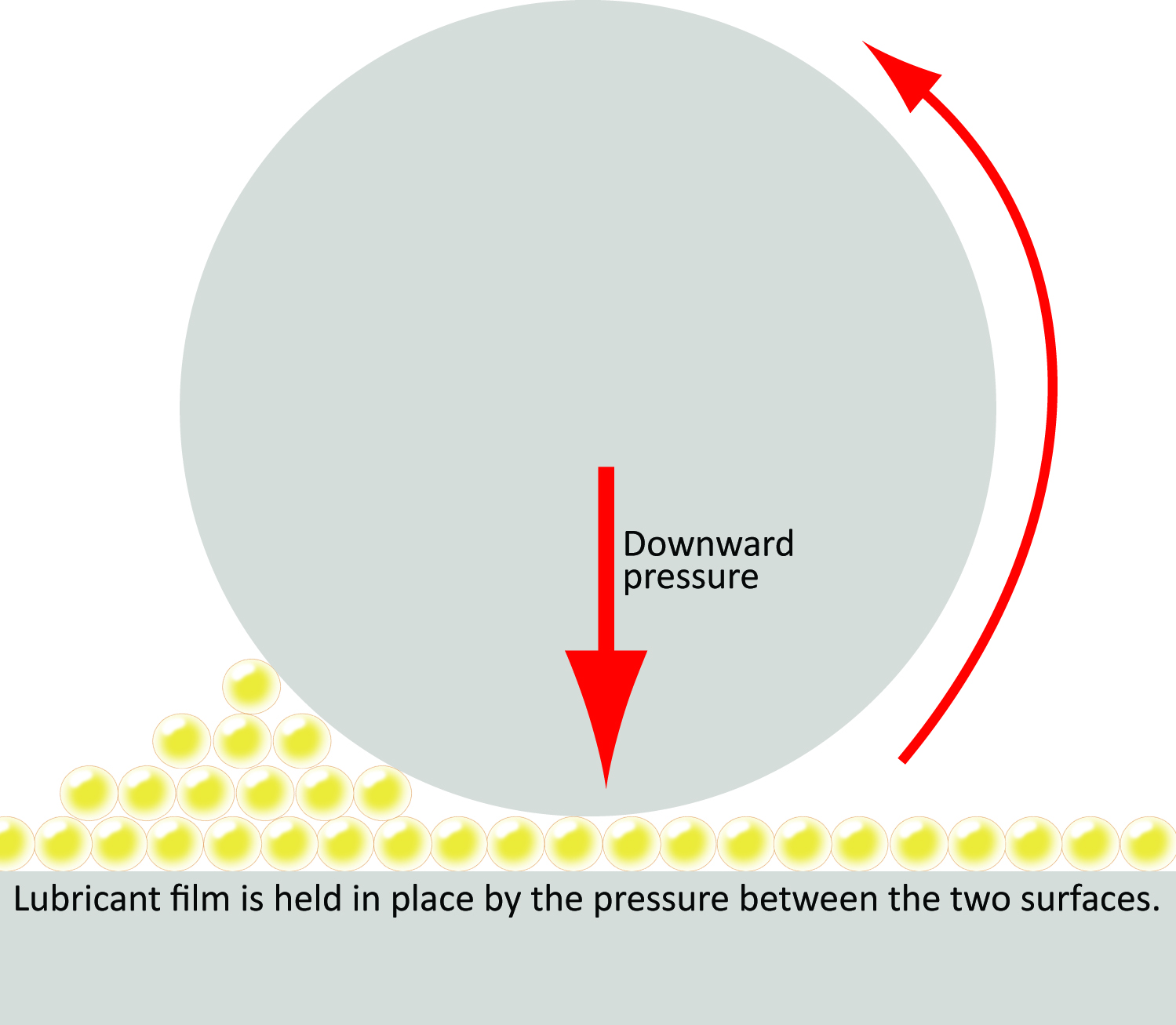

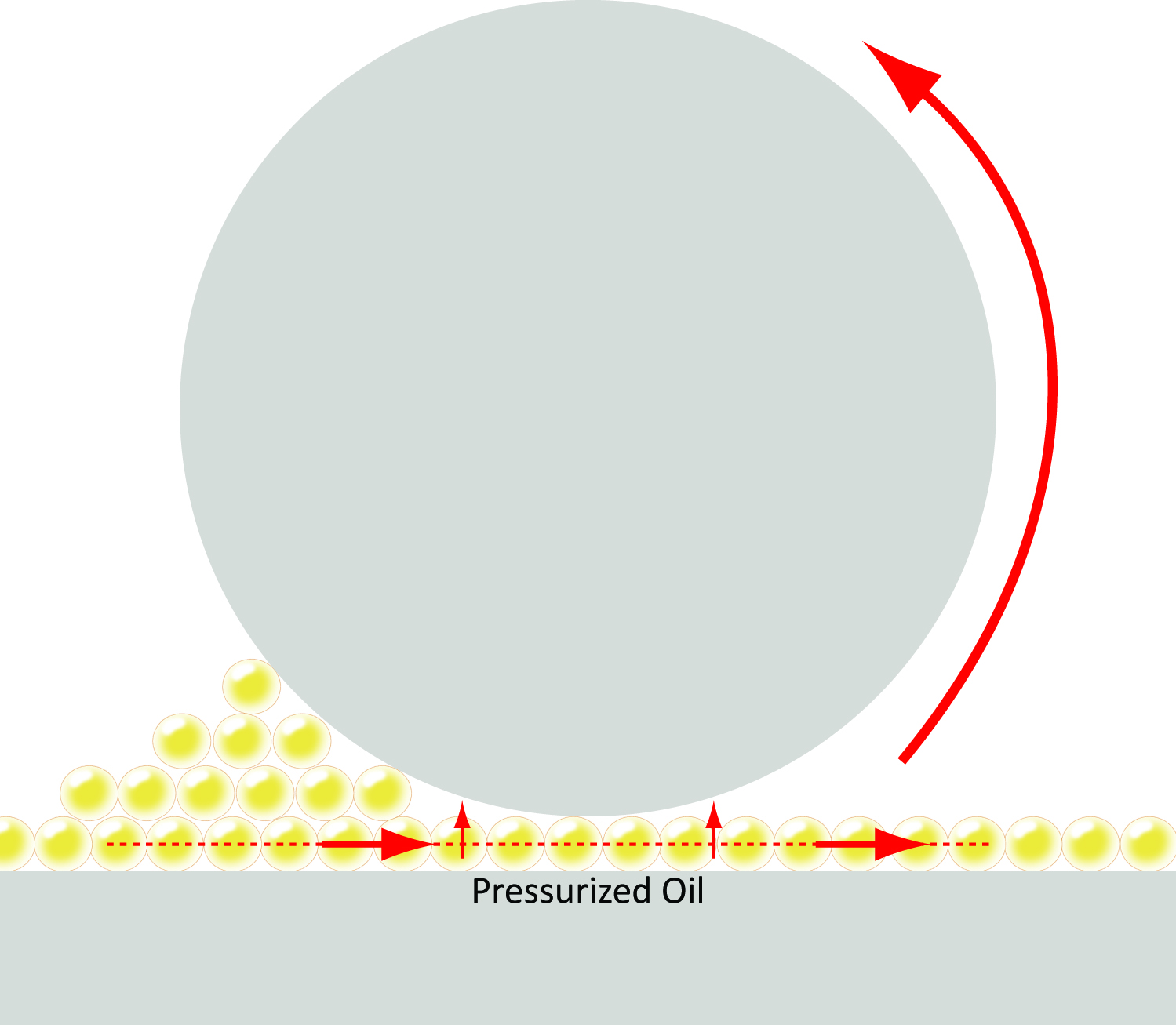

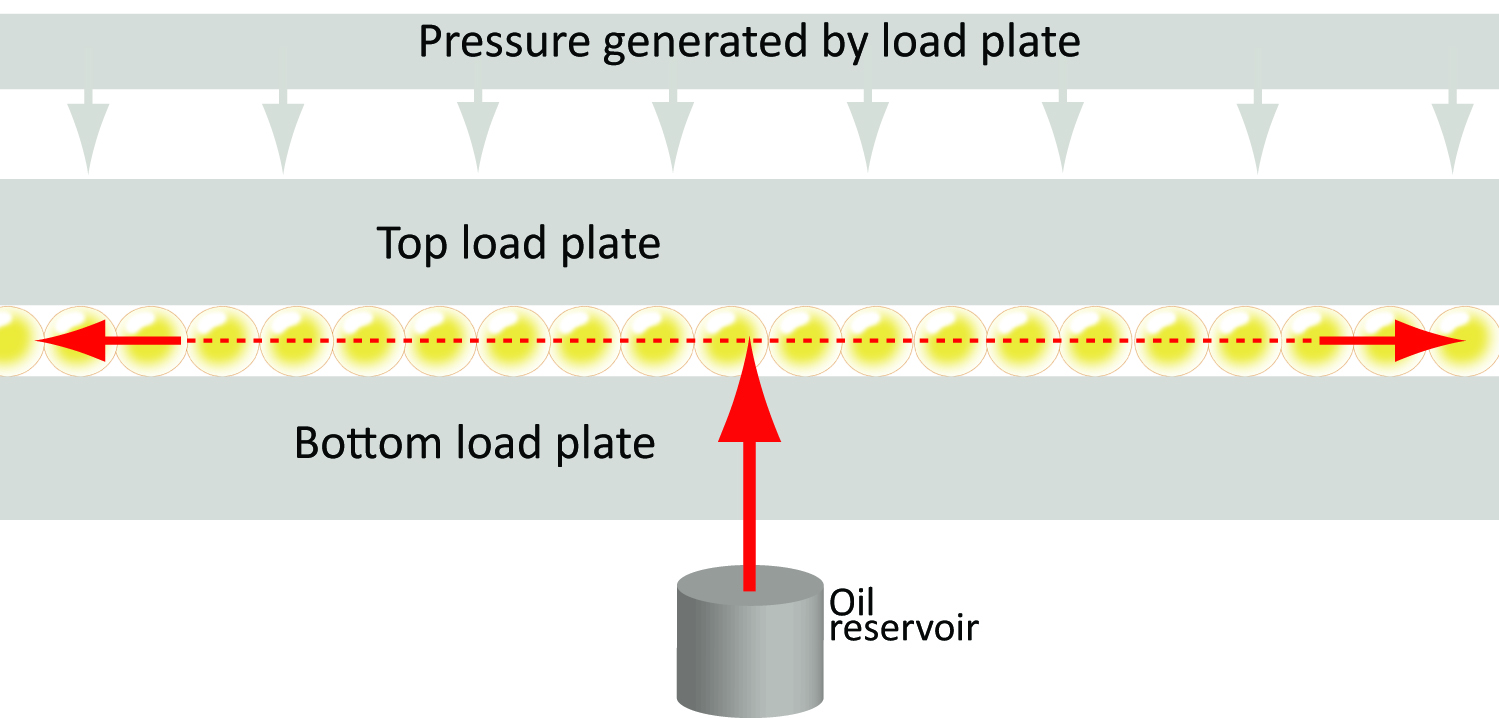

Hydrodynamic, or full-film, lubrication exists when two surfaces are completely separated by an unbroken lubricant film so there is no metal-to-metal contact. The movement of the rolling or sliding action causes the film to become thicker and pressurized, which prevents the surfaces from touching.

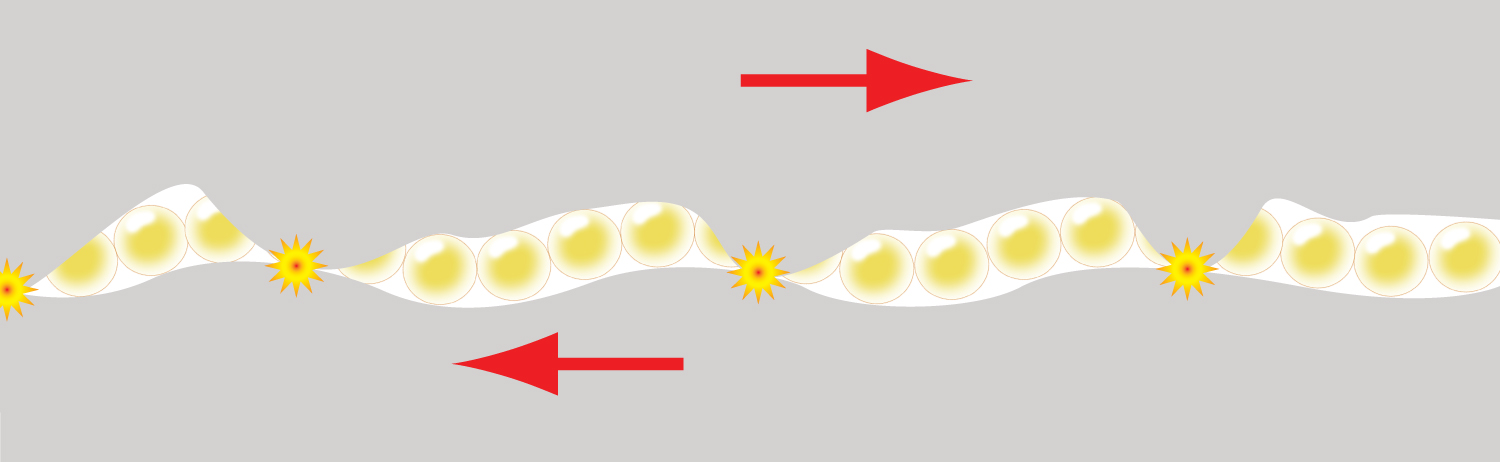

When the two surfaces are moving in opposite directions, the fluid immediately next to each surface will travel at the same speed and direction as the surface. If two parts are moving in the same direction, a full hydrodynamic film can be formed by wedging a lubricant between the moving parts. Known as wedging film action, this principle allows large loads to be supported by the fluid. It works much like a car tire hydroplaning on a wet road surface. During reciprocating motion, where the speeds of the relative surfaces eventually reach zero as the direction changes, the wedging of the lubricant is necessary to maintain hydrodynamic lubrication.

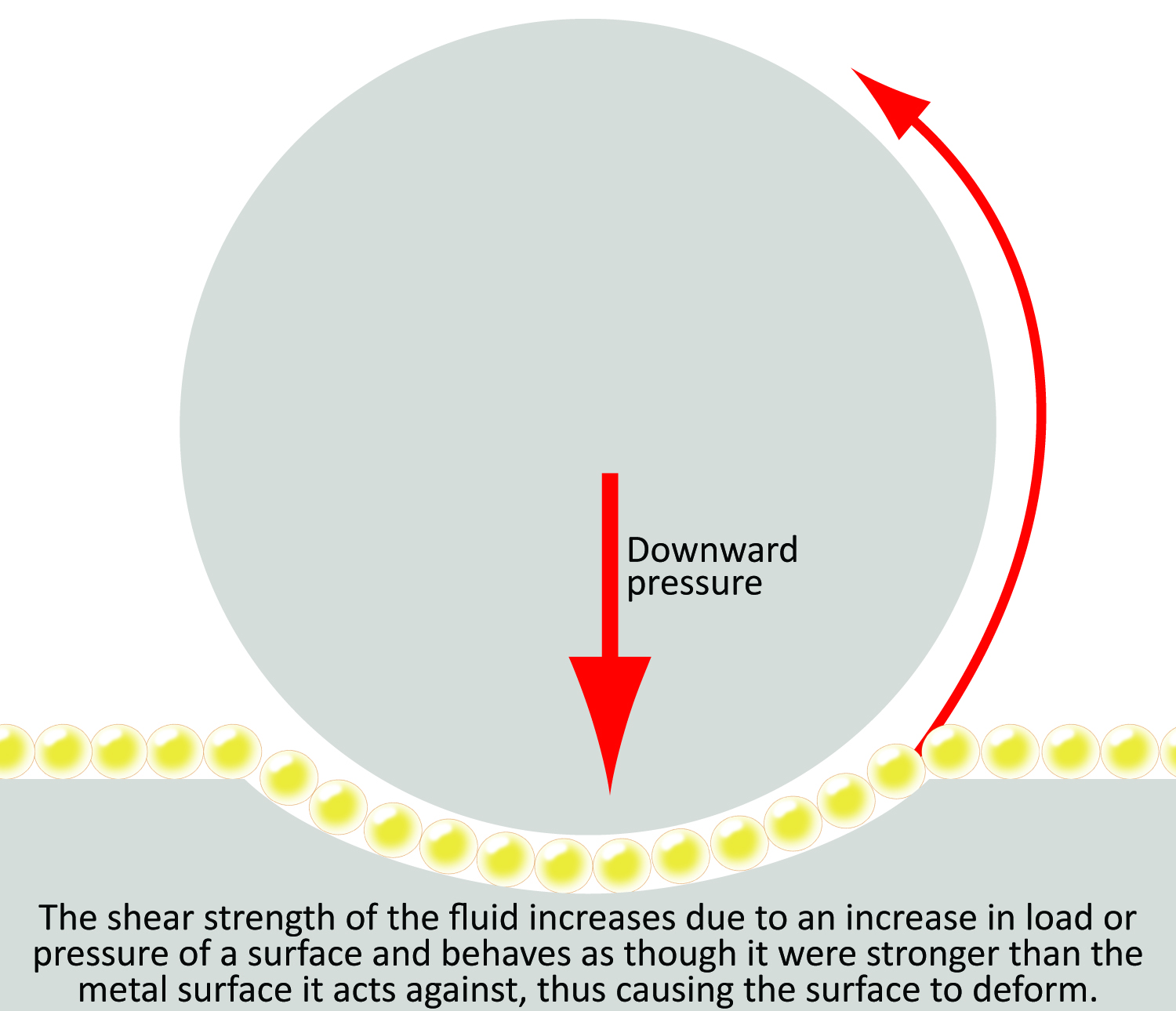

The lubricant’s viscosity assumes responsibility for most of the wear protection and additives play a limited role. Although full-film lubrication prevents metal-to-metal contact, abrasive wear or scratching can still occur if dirt particles penetrate the lubricating film. Additional factors, such as load increases, can prevent hydrodynamic lubrication by decreasing the oil film thickness, allowing metal-to-metal contact to occur.

Engine components operating with full-film lubrication include the crankshaft, camshaft and connecting rod bearings, and piston pin bushings. Under normal loads, transmission and rear-axle bearings also operate under hydrodynamic lubrication.

Comments

AMSOIL Technical Writer and 20-year veteran of the motorcycle industry. Enjoys tearing things apart to figure out how they work. If it can’t be repaired, it’s not worth owning.

Share: